Creativity Returns

Another year is upon us and, with it, an excuse to leave behind old things and consider something new. This has certainly been the case for me as there are just two resolutions I will aim to stick to this year. The first is to avoid following the news, and the second is to play with video production the same way I used to play with software development; fast and loose.

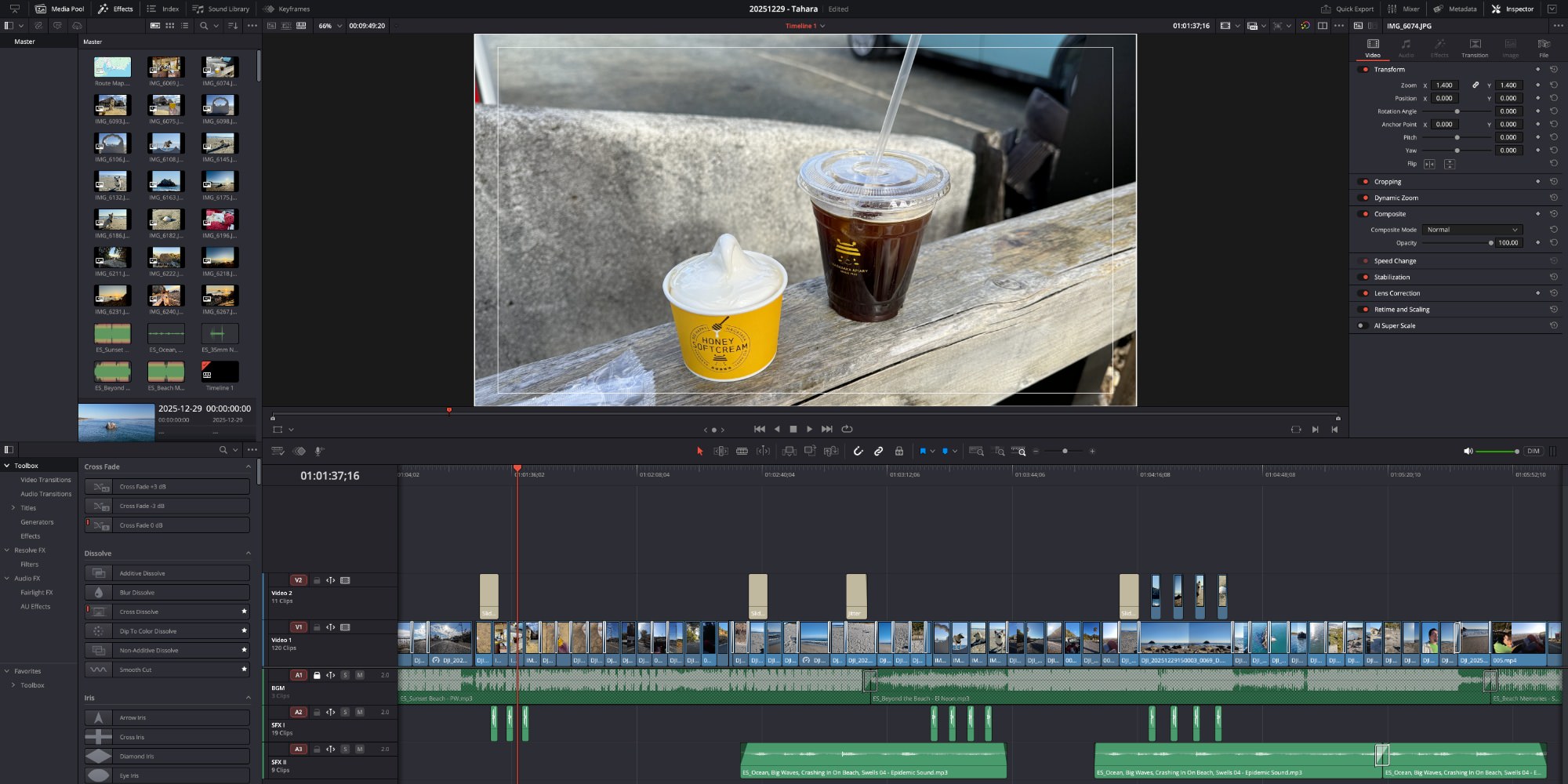

During the final weeks of 2025, I started to notice that my creativity was once again starting to manifest. For the first time in what seemed like forever, I wanted to sit in front of the computer again. Not to write code, not to write blog posts, but to work with video files. I would find an audio track on EpidemicSound, pull it into DaVinci Resolve, and begin the process of putting image to sound. No storyboards. No real plan beyond "put stuff from this directory to music". It was interesting, and it was scratching an itch.

There's something truly wonderful about starting with a blank project at noon and realizing long after the sun has gone down that not only have you forgotten to eat dinner, but you're not even hungry because the very act of creation has satiated the soul. Yes, this does result in some rather boring days for Ayumi, though I do try to bring her outside for walks every few hours to disrupt the monotony of her days. However, the skills that I am picking up by playing around with the photos and videos I've captured over the past few years has been incredibly educational and rewarding.

Heck, just thinking about some of the audio files I have bookmarked for later makes me want to grab the handful of cameras I still possess to run outside and record some more footage.

The videos I end up sharing with the world are not at all professional-grade by any stretch of the imagination. There are obvious issues with lighting, colour grading, timing, and repetition. However, looking at the changes that take place with each upload, I can see there is a clear pattern emerging in the sorts of videos I assemble.

Ten years ago I used to balk at the idea of putting things on YouTube. Perhaps a decade ago it was for the best. Now, though, I can see a great deal of potential with effective video production. It won't pay the bills. It won't provide any monetary ROI. But it will certainly allow me to create things that might actually stand the test of time in ways that my writing and coding never could.

Hopefully this creative spurt will not run out of momentum for months or years to come.